It’s Henry Miller Time: a new study by David Calonne

One has to be a lowbrow, a bit of a murderer, to be a politician, ready and willing to see people sacrificed, slaughtered, for the sake of an idea, whether a good one or a bad one.

Henry Miller (1891 – 1980) had no use for politics, unless you believe the personal is political, in which case he was acting out the change he wanted to see in the world. When he was 33 he dropped out (he was someone with a crucifixion complex), quitting his job at “The Cosmodemonic Telegraph Company” and taking a vow of poverty so he could write. It takes time and energy to write, and those are in short supply if you have a job. I wouldn’t say he worshipped poverty, he just knew the consequences of trying to be a writer—particularly one with soul. He didn’t have a bank account until he was sixty—partly because he had no money and didn’t like banks.

By the time he moved to Paris in the 1930’s, World War I had come and gone and it was now the Great Depression. That is enough to make anyone question civilization and one’s role in it. He preferred culture, saying “Civilization is the arteriosclerosis of culture.” He found his voice by writing about his life and those around him—with an honesty that some found obscene. His books were banned in this country until 1961 (at which point he was 70 years old). I wonder what the population was being protected from—the thought of him walking around with a towel hanging from his erection, or the more subversive dimensions of a freethinker.

By the time he moved to Paris in the 1930’s, World War I had come and gone and it was now the Great Depression. That is enough to make anyone question civilization and one’s role in it. He preferred culture, saying “Civilization is the arteriosclerosis of culture.” He found his voice by writing about his life and those around him—with an honesty that some found obscene. His books were banned in this country until 1961 (at which point he was 70 years old). I wonder what the population was being protected from—the thought of him walking around with a towel hanging from his erection, or the more subversive dimensions of a freethinker.

I have read a number of his books, but it was a long time ago—when my knowledge and experience were less. I recently read Steppenwolf by Herman Hesse (having read it in college), and it was revitalized in my mind. I thought it was time to do the same with Henry Miller (who read Hesse in German in the 1940’s, and got Siddartha translated). With that in mind I went to City Lights the other night (Dec. 16) to hear David Calonne talk about his new book, Henry Miller, from the Critical Lives series.

It was a rainy night and there were about twenty of us on the second floor listening to Calonne. He spoke for an hour and seemed reluctant to stop. Miller was a forerunner to the Beats in some respects, dropping out of the rat race for the sake of writing, along with wine, women, and satori. He didn’t use drugs or drink himself to death. He was more interested in the “divine spark in the material body,” and referred to himself as a “Zen addict.”

Water-colors were more real to him than money. He found writers with a negative point of view to be less interesting or less useful, and thought Walt Whitman had it over Dostoyevsky with his cosmic consciousness.

Water-colors were more real to him than money. He found writers with a negative point of view to be less interesting or less useful, and thought Walt Whitman had it over Dostoyevsky with his cosmic consciousness.

Calonne also wrote a book about Charles Bukowski, and said the two of them had similarities. They were German-Americans with a tough lower middle class background who suffered from strict parents (with Bukowski it was his father, while Miller had a “dumb Germanic cruel” mother). Both were monitored by the FBI, and lived in Los Angeles at some point, with Miller spending the last 18 years of his life in Pacific Palisades. Before that he lived for many years in Big Sur (writing Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymous Bosch, among other books). I had wondered how he came to live in California, having spent the first half-century of his life in Brooklyn and Europe. Turned out it was accidental—he followed a woman to the West Coast.1

I was in Los Angeles in the early 1970’s, and never tried to visit Miller. I was probably being realistic, being only 20 in 1972 and not much of a writer, while he was 81 and the author of 60 books. I wanted to talk with him, however, and we may have had some things in common. I had an old typewriter, a French girlfriend, and a low income, while feeling like a man without a country.

Calonne gave us an outline of his life, and mentioned that his mother, sister, and aunt were mentally ill. Miller worried about being schizophrenic, and had a recurring nightmare of looking in the mirror and seeing someone else, then being arrested and trying to talk but no one understood him. He even had a momentary identity loss, a black-out of some sort.

In 1913 he left Brooklyn for New Mexico and California, supposedly as a cure for being nearsighted. I’m not sure how that works—the wide-open spaces in the West improve your vision? He wanted to be a cowboy, but it didn’t work out, and he returned to Brooklyn with his tale between his legs.

In 1913 he left Brooklyn for New Mexico and California, supposedly as a cure for being nearsighted. I’m not sure how that works—the wide-open spaces in the West improve your vision? He wanted to be a cowboy, but it didn’t work out, and he returned to Brooklyn with his tale between his legs.

In 1930 he moved to Paris and started working on Tropic of Cancer, which he characterized as “First person, uncensored, formless—fuck everything!” I asked Calonne during the Q and A how Miller got by in Paris—he was there for most of the 1930’s. He stayed with friends, did some proofreading, and may have written pornographic stories. I have been in Paris with little or no funds, but only for a few days. When you’re not eating much, the statues and the gothic churches take on a delirious aspect. Miller may have been seeing angels, with one of them materializing in the form of Anais Nin.

She supported him for much of the time he lived in Paris, being married to a well-off banker who didn’t mind if she slept around and kept a journal (as long as she didn’t write about him). Her journals were full of poetic license. Gore Vidal said she couldn’t be trusted, and so did she: “I tell so many lies I have to write them down and keep them in the lie box so I can keep them straight.” Maybe she was, as Cocteau said, “a lie that tells the truth.” At any rate, she paid for Miller’s first book to be printed.2

She supported him for much of the time he lived in Paris, being married to a well-off banker who didn’t mind if she slept around and kept a journal (as long as she didn’t write about him). Her journals were full of poetic license. Gore Vidal said she couldn’t be trusted, and so did she: “I tell so many lies I have to write them down and keep them in the lie box so I can keep them straight.” Maybe she was, as Cocteau said, “a lie that tells the truth.” At any rate, she paid for Miller’s first book to be printed.2

During this time he wrote Tropic of Cancer (1934), Black Spring (1936), and Tropic of Capricorn (1939). He was reading the Tibetan Book of the Dead and studying Buddhism. Calonne said he was one of the most widely-read American authors at the time, more like Thoreau and Emerson and less like Steinbeck or Hemingway. Novels were secondary to him in his studies. He was theosophical, believing in an ancient wisdom passing through the centuries. It is out there, but it may not make it through Customs.

He read Madame Blavatsky, a dubious clairvoyant known to Yeats and D.H. Lawrence. Miller was obsessed with Lawrence. He tried to write a book about him, but couldn’t figure him out and finally abandoned the study.

H.L. Mencken admired the precision of his writing and thought him first-rate. George Orwell wrote an essay about him in 1940, “Inside the Whale,” referring to him as “…the only imaginative prose-writer of the slightest value who has appeared among the English-speaking races for some years past.” He also said, “He is a completely negative, unconstructive, amoral writer, a mere Jonah, a passive acceptor of evil, a sort of Whitman among the corpses.”3 Orwell may have been referring to Miller’s apolitical leanings, which his own politicized mind regarded as passive and amoral. I don’t think writing books is passive, but it’s true that Miller never fought in any wars. Maybe he didn’t like corpses.

Orwell came close to canceling most of his books before they were written when he fought in the Spanish civil war and was shot through the neck. Henry had warned him not to go. He greatly admired a book like Down and Out in Paris and London (1933), but considered Orwell to be a political idealist—of which he never saw the point.

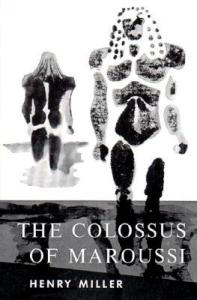

In 1940, Miller was forced to leave Europe because of World War II. He returned to the States, having been away for ten years, and wept when he arrived in Boston. It wasn’t Paris or an island in Greece.4 He was broke and wearing cast-off clothes. He wrote The Colossus of Marousi (1941) in the back of a synagogue, about the time he spent in Greece. He considered it his best book and there is notably no sex in it. Norman Mailer (in Genius and Lust) thought he wrote the book to “Greece” his way into more respectable literary circles.

In 1940, Miller was forced to leave Europe because of World War II. He returned to the States, having been away for ten years, and wept when he arrived in Boston. It wasn’t Paris or an island in Greece.4 He was broke and wearing cast-off clothes. He wrote The Colossus of Marousi (1941) in the back of a synagogue, about the time he spent in Greece. He considered it his best book and there is notably no sex in it. Norman Mailer (in Genius and Lust) thought he wrote the book to “Greece” his way into more respectable literary circles.

He bought a 1932 Buick for $100 and drove around the country for a year. Out of this came The Air-Conditioned Nightmare (1945). He was disturbed by what he found, like “weird insects pretending to be men” and a factory full of “insane sounds.” His advice: BOMB DETROIT. He found the art of living was still practiced in some areas of the south, but otherwise the culture was depressing. Publication of the book was delayed for several years—it was thought too negative to be published while the country was at war.

Miller met Aldous Huxley in Los Angeles, along with John Cage (they stared at each other for 4 minutes and 33 seconds and then walked away, or maybe not). He met Dali and didn’t like him (something about the persistence of monarchism). By the early 1940’s he was in Big Sur. This was the period when The Rosy Crucifixion trilogy was published (1949 – 1959). He lived there until 1963 (moving to Los Angeles when he could finally afford to buy a house) . Kerouac was going to visit Miller in Big Sur, but got drunk in Vesuvio’s instead, which is across the alley from where we were listening to a talk about Henry Miller.

He thought his source of power was Jupiter, rather than Christ, and that it would be around much longer. Talk about cosmic consciousness.

“The world dies over and over again, but the skeleton always gets up and walks.”5

Notes

- His middle name is Valentine, which might explain a few things. His love of women is legendary—partly because he wrote the legend himself. From the interview in the Paris Review: “… in France woman plays a bigger role in man’s life. She has a better standing there, she’s taken into consideration, she’s talked to like a person, not just as a wife or a mistress or whatnot. Besides, the Frenchman prefers to be in the company of women. In England and America, men seem to enjoy being among themselves.”

- Calonne said he wrote his book to refute the one-dimensional view of Miller as someone who is obsessed with sex. That description might apply to Anais Nin, who managed to be on erotic terms with her own father (as a grown woman).

- It is more negative to reduce everything to a political equation or dogma, not to say absurd. When Orwell fought against the fascists in Spain he was accused by the Communists of being “’objectively’ Fascist, hindering the Republican cause,” and all because the faction he was with was thought to be Trotskyist.

- A friend of mine is a writer in her 30’s who grew up in Brooklyn. Her ancestors are from Italy and she loved to go there. Returning to Brooklyn she would break into tears.

- “Uterine Hunger,” The Wisdom of the Heart (1941)

—

Steven Gray has been living in San Francisco since 1849 and has rent control. Self control is another matter. He reads his work on a regular basis in venues throughout San Francisco. Sometimes he accompanies other poets on guitar. He is co-editor of Out of Our, a poetry and art magazine, and has two books of poetry: Jet Shock and Culture Lag (2012), and Shadow on the Rocks (2011)

Steven Gray has been living in San Francisco since 1849 and has rent control. Self control is another matter. He reads his work on a regular basis in venues throughout San Francisco. Sometimes he accompanies other poets on guitar. He is co-editor of Out of Our, a poetry and art magazine, and has two books of poetry: Jet Shock and Culture Lag (2012), and Shadow on the Rocks (2011)

Sexus is one of my all-time favorites. . . Thank you thank you!!

Dear Steven, Miller was extremely important to me when I first started out as a writer. (Important for his breaking through so many of the falseness’.) Later I realized that I read him like a man, I mean, as if I was a man. I certainly was not one of the cunts he fucked and so denigrated. I’ve thought and written a lot about him and this perspective, reading him as a man, and though this thinking was harrowing at the height of my education on sexism, I have never abandoned my deep appreciation of his writing, and have always felt that once we evolve through the absolutely necessary recognition of the universal sexism we will welcome him back. In some ways, I’ve felt the same with Bukowski–the magnificent LA writing! I stop regularly, still, at the Henry Miller Museum in Big Sur. Anais Nin was also important to me back then, I read all her diaries, but her dishonesty–in her diary!– compared to Henry, was hard to swallow. And her sexual relationship with her father, ugh. But at least she discussed it, which back then felt like, finally, honesty. Once back then too I had a job with a Beverly Hills playwright going blind–I helped her organize her stuff–who was long time friend of Henry Miller’s. I can still hear his voice when he telephoned and asked for her.

Wonderful response, Sharon. I remember a woman telling me that Norman Mailer was a sexist writer. I asked her if she had read any of his books and she said no.